I was reading a well-known and highly regarded book about a significant Jewish spiritual practice when I stumbled onto the following passage:

The Hebrew term for gratitude is hakarat ha’tov, which means, literally, “recognizing the good.” The good is already there. Practicing gratitude means being fully aware of the good that is already yours.

If you’ve lost your job but you still have your family and health, you have something to be grateful to be grateful for.

If you can’t move around except in a wheelchair but your mind is as sharp as ever, you have something to be grateful for.

If your house burns down but you still have your memories, you have something to be grateful for.

If you’ve broken a string on your violin, and you still have three more, you have something to be grateful for.

I was instantly struck by the ableism in this passage. I really wanted

to be wrong, so I quickly snapped a photo and sent it off to a trusted friend/colleague/disability

advocate who confirmed what I already knew. Her words, “That line is

so problematic. People are so quick to pit physical and cognitive disabilities

against one another and to create an arbitrary hierarchy of disability. There

were so many other examples the author could’ve used. I agree with you - that

one misses the mark entirely.” Sigh.

I became profoundly sad, realizing thousands of my colleagues

- clergy, educators, and other prominent leaders - have read these words and

absorbed them matter-of-factly, moving on to the other “more important”

messages of the book. THIS is the pervasiveness of ableism, and I think the

first step toward eliminating it is for each of us to come to recognize it.

So let’s start from the beginning. Ableism is defined by The Center for Disability Rights, Inc. as a set of beliefs or practices that devalue and discriminate

against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities and

often rests on the assumption that disabled people need to be 'fixed' in one

form or the other. An ableist society

treats non-disabled people as the standard and allows for discrimination to

occur against those who are disabled by inherently excluding them.

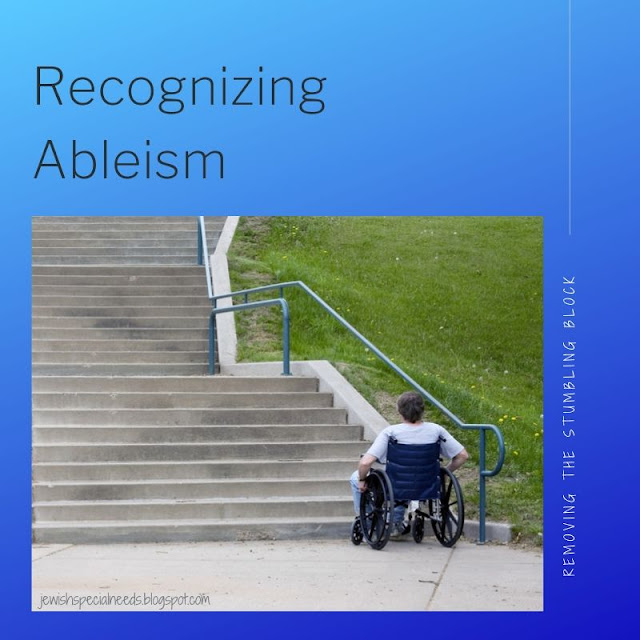

We also need to understand the difference between the medical and social models of disability to fully recognize ableism. The medical model (most common way to define disability) states that people are disabled based on their impairments or differences. This places the “problem” of disability on the disabled individual, making it their responsibility to “fix” themselves in order to participate in an able world. The social model of disability, however, helps us to reframe our understanding of disability as a product of social and physical environments. A wheelchair user is fully able in their home that accommodates them. It is only when faced with a building without ramps that they become disabled (unable to participate). Viewing disability through the medical model can promote ableism.

Here are two clear examples of ableism:

2) Ableism is embedded in the English language. Words like “lame”, “crazy”, and “idiot” have a history of discrimination toward people with disabilities and perpetuate the assumption that disability is a detriment. The language we use towards and about disabled individuals (“wheelchair bound,” “suffering from”) disregards their autonomy. Equally as significant as the language used is what the use of such words & phrases suggests the speaker feels about the individuals these represent. When a society's language is full of pejorative metaphors about a group of people, those individuals are more likely to be viewed as less entitled to rights such as housing, employment, medical care, and education. The use of language that perpetuates the assumption that disability is a detriment is ableism.

We must

work to make sure there is always a seat at the table for everyone. Then we

need to consistently check ourselves to be sure we treat people with

disabilities with kindness, dignity, and respect once they are at the table. Combating

ableism can be as simple as treating disabled people as you would anyone else.

Educate yourself about disability. If you don’t have a disability or you’re not close to a person with a disability, take it upon yourself to learn. Remember that disabilities come in a wide array of shapes & sizes and affect people in many different ways. Part of being a good ally is arming yourself with knowledge about the issues and challenges people with disabilities face every day.

Interact with disabled people. Many people are afraid to interact with a disabled person for fear of saying or doing the wrong thing. First, understand that someone with a disability is just a person. Like anyone else, they have unique personality traits, likes and dislikes, and hopes and dreams. They have good days and bad days. They might crave social interaction during certain times and prefer a quiet space or a break from talking at others. Treat disabled people the way you would like to be treated. Ask before offering assistance; don’t assume a person wants or needs help. Speak directly to a person with a disability rather than to their caregiver or companion; don’t treat the person as a child or someone to be pitied. Treat assistance and service animals with respect, recognizing that they are working animals, not pets. Finally, refrain from being too inquisitive about an individual’s disability.

Finally, speak out. It may not be easy, but pointing out ableist language and behavior to others in kind and respectful ways can help them to recognize and make their own changes as appropriate.

I realize that my next step must be to reach out to the author of the prominent book I mentioned at the beginning of this post. I hope that pointing out the ableist language he used will help him to understand so that he shifts his language going forward.

What steps will you take to eliminate ableism?

Make sure you never miss a post from Removing the Stumbling Block:

No comments:

Post a Comment